Chaplain’s Time: Darkest Hours Series: Religion

St. Petersburg Times – St. Petersburg, Fla.

Author: SUSAN WILLEY

Date: Dec 3, 1994

I believe in the sun, even when it is not shining. I believe in love, even when I don’t feel it. I believe in God, even when he is silent. – Words on a cellar wall in Cologne, Germany, after World War II. The message is above Chaplain Pete Church’s desk.

When the Rev. Pete Church hears his name over the hospital paging system, he listens carefully. The news is usually not good.

He catches an elevator or dashes down the stairs to where he is needed. It may be that a child was struck by a car, or a man was shot. Perhaps there is a drowning victim in the emergency room or someone in intensive care has gone into cardiac arrest.

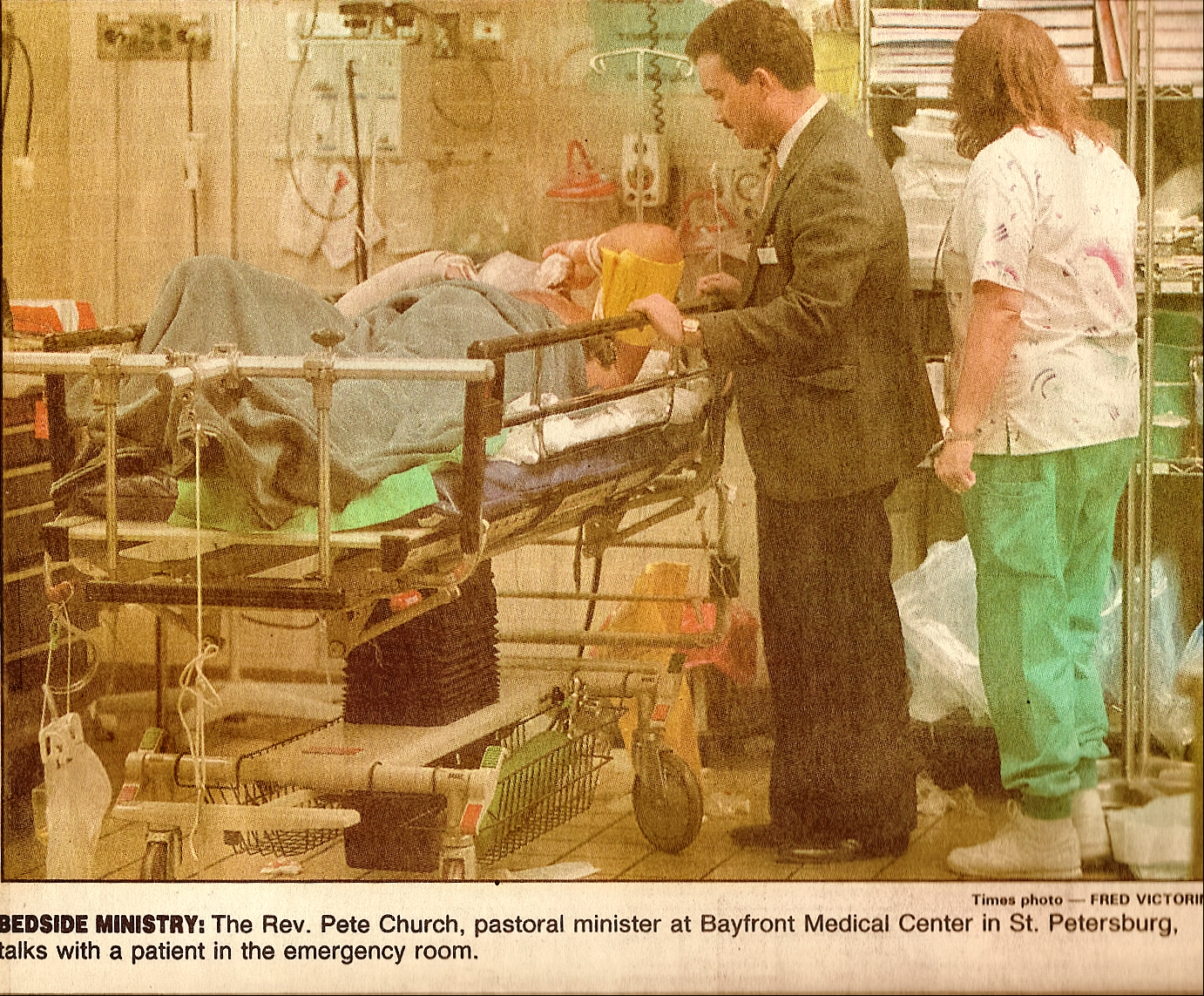

Church, 39, has seen all this and more during his three years as a hospital chaplain. After serving eight years in the military, he currently is a chaplain in the U.S. Army Reserves. He also is a staff chaplain at Bayfront Medical Center and has a contract with All Children’s Hospital.

He has experienced the grief and shock at the sudden passing of a young life, and he has shared the joy and relief at an unexpected recovery.

His job skirts the deepest mysteries of life and death. He enters the lives of grief-stricken families as a stranger, but soon becomes their lifeline and confidant.

Born in Montgomery, Ala., Church’s father was an Air Force fighter pilot. The family moved frequently, but was in Florida in 1974 when Church graduated from St. Petersburg High School. In his teens, he was a three-time state weightlifting champion. He also taught himself to play the guitar. He recently released a recording of contemporary Christian songs that he wrote.

“The songs deal with the hard facts of life and how we manage to get through them with our spiritual resources,” he said.

After he graduated from the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky., he was pastor at a small church for a year and then began his clinical training as a chaplain. He now lives in the Kenwood neighborhood of St. Petersburg.

At Bayfront, Church is often the first person who contacts family members. He is there for people people facing their darkest hour, as they struggle for meaning in the midst of tragedy. As a minister, he must serve as a representative of faith in a time when people no longer trust the concept of a loving God.

The holiday season is often the busiest time of the year for hospital chaplains, he said. Tragedies are hard to handle any time of the year, but at Christmas grieving is intensified.

“It’s supposed to be a happy time of the year, and suddenly it is not,” he said.

The most difficult are the deaths of children.

“They are the innocents,” he says. “They don’t understand the dangers in the world. They are the most vulnerable. They think they are invincible, and they have not done anything to deserve what has happened to them.”

Church understands. He knows the pain of losing a child.

It was Memorial Day weekend 1983 in Riverside, Calif. Church and his wife, Jane, decided to go out one afternoon to celebrate their wedding anniversary. Their neighbors agreed to babysit their two children, Jennifer and Spencer. Church remembers they were gone less than three hours. When they returned, their world had changed forever.

Four-year-old Spencer had been riding his bicycle when he wandered onto a busy street and was struck by a car. He was in a coma for four months with massive injuries. When he eventually came out of the coma, he was severely impaired – mentally and physically.

“He was blind and had the mentally capacity of a newborn,” Church said. “He was paralyzed from the chest down. He was just a shell really.”

March 10, 1987 – nearly four years after the accident – Spencer died in his sleep.

Why did God let this happen? The question is a familiar one for people in grief. The question is one Church, as both a father and a minister, kept asking.

“When I look at the ideals of the Christian faith and then I look at the reality of human pain and suffering, I realize there is a tension there,” Church said. “It is a struggle I will have all my life, trying to reconcile this.

“I was brought up to believe in a good God who looks out for you and will protect you. So when something bad happens, you ask `God, where were you? And why didn’t you stop it? What terrible thing did I do to deserve this?’ “

After years of study, prayer and struggle, Church says he still may not understand God’s ways, but he strongly believes in God’s love.

“I tell people that I believe God suffers right along with us and with the children because God loves us and loves the children. I see God as a very loving God, but he has created the world as it is, imperfect.”

Church survived the tragedy and kept his faith partly because he began a long journey of introspection that reinterpreted his idea of God and life.

“I no longer think of God as Santa Claus. He is not there to give me everything I want, when I want it. He is not there so much to keep the bottom from falling out as to be there to catch us as the bottom falls.”

Because of his own experience, he empathizes with people in grief. He calls it “a double-edged sword.”

“It’s both a blessing and a curse,” he said. “But the bad that has happened is just the thing that makes me a good chaplain. That doesn’t mean I like what has happened. If I could change it, I would. I would much rather be blissful and ignorant than experienced and tried by fire.”